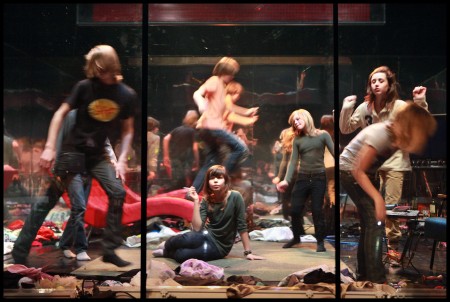

Gob Squad’s Before Your Very Eyes combines two of the 2012 Theatertreffen’s “remarkable” aspects: time and collectives. More specifically, this transnational performance collective raises questions about the subjectivity of time.

Time and Collectives: Gob Squad. Photo: Manuel Reinartz

Before Your Very Eyes is a performance with seven teenagers who perform their lives in fast forward. In the “safe environment” of a glass house, a voice from above guides them through their lives. It also confronts them with questions and challenges on their way from puberty to mid-life crisis and ‚til death do them part. Their journey into the future is linked to the past when the kids are faced with interviews with themselves – recorded when they were two years younger.

The following interview might serve a similar purpose some years from now, as I talked to Simon Will, one of Gob Squad’s seven core members since 1999, about life’s challenges and changes.

Undisguised: Simon Will from Gob Squad. Photo: Adrian Anton

Adrian Anton: The very entertaining Gob Squad FAQ pages host interviews and frequently asked questions. In one of the videos there you state that you as performers are not representations of something – but isn’t any public speaking or acting always a representation of something?

Simon Will: It’s a question of how you define „representation“. Of course we are performing aspects of ourselves on a stage or in front of a camera, which is different from the „self“ sitting here talking to you. Although in the expanded sense of the word I am still performing: I am performing talking to you, we are performing an interview, and it is somehow artificial. But it’s nice to have that expanded idea of performance happening all the time. I even wonder if it’s accurate or helpful to say that we are representing ourselves up there on stage. Because we aren’t speaking on behalf of ourselves in the sense of: I am a white, gay, middle-aged man. You can take aspects of me and be tempted to say that that what I represent. Of course you can’t be separated from what you are, but actually I’m not speaking on behalf of any one of those attributes. You might have an accordance with what I say or you might not. It’s as simple as that and that’s as far as it goes.”

A.A.: Before Your Very Eyes implicitly asks how, why, and when life turned out wrong. Do you think that everybody comes to a point in life when you ask those questions?

S.W.: When we were making the work we had a lot of discussions and debates about that question. I think that to a smaller or greater degree that’s something that a lot of people can relate to. I wonder, if there was a twenty-year-old me, listening to me now, what would that twenty-year-old me would have to say about that? Because in some ways as a twenty-year-old I was much more of a fundamentalist in some ways: in terms of what I expected from life, what I expected from people, what I expected from the world. Although I still look at the world and see things that are frustrating and that I find unfair, as a teenager the weight of that was immense, and somehow this weight has come off me.

A.A.: Can you name any particular influences for Before Your Very Eyes?

S.W.: One of the big influences or inspirations for Before Your Very Eyes was a film by Charlie Kaufman, Synecdoche, New York. It’s a story about a theatre director living in New York with his family who reaches middle age, starts thinking he’s getting ill, and his whole life falls apart as he’s moving towards death. Some of the opening lines of the show that deal with death actually come from this film. Some think this film’s really devastating, but on some level it is really quite elevating. The first thing the film says is: everybody is disappointed. You carry around this ideal of someone or something and in the end they disappoint. It’s about the question: What was I expecting from life? Hopefully the way those seven kids on stage enact those clichés about how life is supposed to be and those rites of passage works on more levels than just to create a sense of devastation.

A.A.: I believe this device of putting kids on stage makes it easy for people to relate to the play. Another interesting device is this guiding but non-omniscient voice, what was the idea behind that voice?

S.W.: The idea of the voice came through working on the piece. In this work we had to deal with practical things we were not accustomed to at Gob Squad. First of all we’re not accustomed to writing scripts. We normally never work with scripts. Although we often work with a structure or a set of events, we found it very difficult to work with texts. Normally we don’t need scripts in order to give room to developments and we have the freedom to fill the spaces according to our needs.

Martha Balthazar, Spencer Bogaert, Zoë Luca, Faustijn De Ruyck, Gust Hamerlinck, Jeanne Vandekerckhove, Ine Verhaegen. Photo: Phile Deprez

But in this case we couldn’t do that because we knew there would be subtitles. That was already a kind of problem for us. So we asked ourselves how we could work around this theatrical device, these subtitles that form a block of text on stage. The solution came by turning it around: usually subtitles tell you what happens on stage. Here it tells the actors on stage what to do. And later the idea of the voice came along.

In the beginning the voice says: „Hi kids! What are you doing? We love to watch you play!“ We as adults tend to look at children in quite a voyeuristic way. So much is projection: Children as our future. So much is expectation. We could sit and watch children play all day long and project things on to them. And then we say: „Grow up!“

The voice is a sort of authority: it’s us, the directors, but it’s also a voice from within. So the voice functions on different levels and can also be seen as metaphorical. I hope that it possibly speaks on quite a few levels.

A.A.: The biography of Gob Squad stresses challenges due to procreation or funding or personal crisis – aspects that usually remain in the private sphere. The theatre scene especially doesn’t seem to pay too much attention to such influences, and common biographies of directors usually only focus on successes. Why do you pay attention to those private aspects in your work?

S.W.: Maybe, especially in German theatre, there’s still a favoritism towards directors, male directors in particular are treated as geniuses. Like a genius complex. But I often look at theatre and the people who are making theatre and I want to ask: how can I make a connection to you and how you made that piece of work and who you work with and your life and your life within the system that you work in?

What I often wonder is whether people reading our biography – in which we include issues of childcare, funding, and all these struggles – take it seriously or see these challenges as small and trivial.

A.A.: Do you think it’s a political question?

S.W.: I know a lot of people look at us and say we are just light and not political. But I totally disagree: I think that we’re very political with our process, with the way we’re handling things, with this different structure than the hierarchical one that is usually in place, and even the way we distribute money among ourselves, the way we make allowances for people with children, but also for people without children who want to go out instead and so on. And all those things are important and political.

The personal is political.

But in theatre those things only seem to matter when they become a big thing, like if someone becomes ill or dies. Like Sarah Kane. You cannot watch these plays without knowing that she died. You cannot separate those aspects.

A.A.: Sarah Kane’s biography has become a public subject. Do you find it more empowering or sometimes also exhausting to address your personal challenges publicly?

S.W.: Personally I can not really imagine it being in any other way. So I don’t know any alternative. For us it is a process, and sometimes we do get very tired from it. But if I think about what came along with our selection for the Theatertreffen is the remark: „Oh, now you are successful.“

But actually the success is that we’ve been working together since we were like 19 years old. Anyone who has ever worked in any kind of collective or any kind of theatre, whether it is hierarchical or non-hierarchical, knows the struggle to negotiate and to try and find your way or build relationships in any kind of context. If anything should be measured as successful, than it’s that. That more than anything, really.

A.A.: As you mentioned success, back in 2010 your website stated: ‘The group are uncertain whether to be flattered that they now seem to be part of official performance art history, or whether this marks their arrival in the mainstream, and therefore the company’s imminent demise.’ Any comments now that you’ve been invited to the Theatertreffen?

S.W.: Well, I think we’ll survive. What I think is really great is that a whole different audience is going to see the play now. It’s like being in a new fish bowl. Our audience is really important to us and our work. We really think about them while doing our work.

A.A.: Do you think the Theatertreffen is going to influence your work or your view on theatre?

S.W.: We don’t think about theatre very much, because we come from a performing arts background. That’s really liberating, because we don’t really need all this. That was the real challenge making „Before Your Very Eyes“, because we really had to think about theatre. But in the end: who cares if this is really theatre? The question is: did you really get into it? Did it speak to you? It doesn’t matter if it’s theatre or sculpture or any other form it comes in. The ritual of gathering a bunch of people together is about creating something. It’s as simple as that!

„Before Your Very Eyes“: zu sehen am 18. und 19. Mai 2012 um 20 Uhr, sowie am 20. Mai 2012 um 15 Uhr im Haus der Berliner Festspiele.