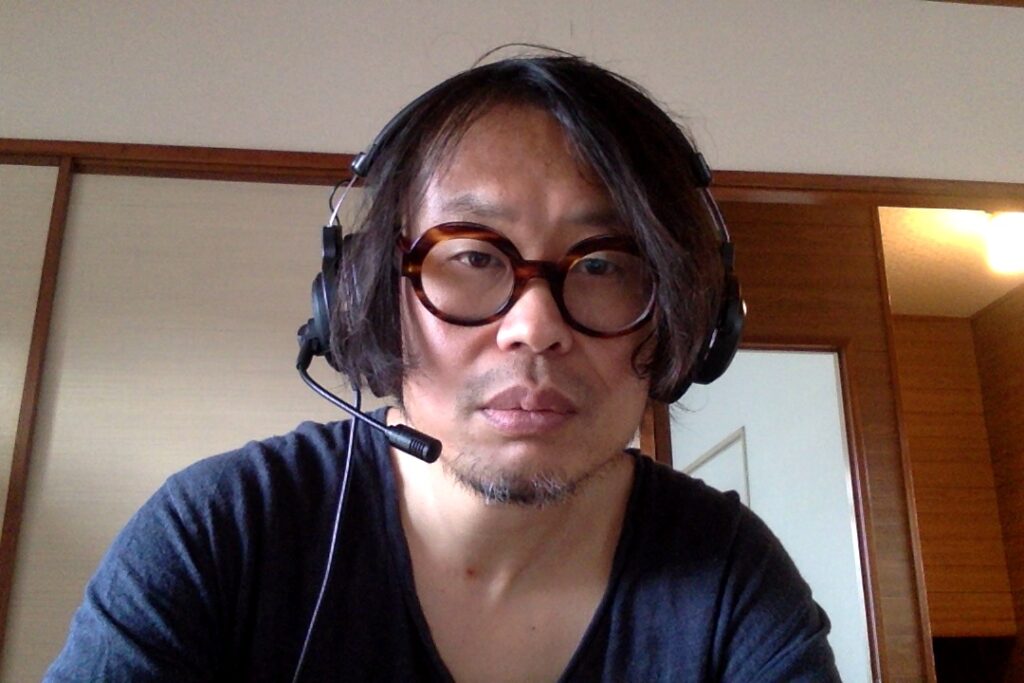

The virtual Theatertreffen completes its streaming run of six of the invited productions tonight with Toshiki Okada’s The Vacuum Cleaner. Here’s what the director told Nicholas Potter about the Hikikomori phenomenon, how the Japanese theatre industry deals with the crisis – and how it has changed his own perspectives.

Toshiki Okada received his first invitation to Theatertreffen this year for The Vacuum Cleaner, a piece about a reclusive family burnt-out by turbocapitalism. In the meantime, the world has come to a pandemic-induced standstill and many of us are forced to seek refuge within our own four walls. Our current predicament certainly reframes Okada’s play, which externalises a family’s internal suffering. Over the past twenty years, the 46-year-old director has developed an idiosyncratic blend of theatre that jumbles music, speech and movement in a highly dislocated fashion, evoking a sense of neoliberal alienation. It’s a style that’s won him fans at home in Japan and abroad: The Vacuum Cleaner is his fourth production at the Münchener Kammerspiele under Matthias Lilienthal. We caught up with Okada to hear about his life under quarantine, a Japanese theatre industry in crisis and the taboo of mental health.

TT-Blog: A month ago, Japan declared a state of emergency in response to the coronavirus pandemic. What’s the current situation?

Toshiki Okada: I don’t think the government is dealing with the situation well. We don’t have a shutdown like in Europe, because the government doesn’t have the power or right to declare one.

The Japanese government has focussed more on a policy of jishuku – or self-restraint. Instead, they have threatened to name and shame businesses that fail to act responsibly during the pandemic. How has this strategy worked out so far?

The government has been asking people to reduce their activity, be it for business or pleasure. It’s not an order, just a suggestion – but most people are following this advice. Some people are working from home but it really depends on what kind of business they’re in. A lot of people still have to go to work though, as it’s impossible for them to work from home.

What does this mean for the theatre industry?

Almost all of the theatres are closed now. I don’t really know when they will open again but there’s an expectation that it will be in autumn.

Are Japanese theatres also making streams of performances available online?

No, they haven’t yet actually. Some independent theatre companies have shown recordings of performances online or even performed live on Zoom, but not to the same extent as in Germany.

Are the creative industries getting support from the Japanese government in the meantime?

The Japanese government doesn’t pay nearly as much attention or respect to the function and importance of the arts as in Europe. I don’t think we can expect any financial support. So many venues, especially private theatres, are already struggling. Some could start closing down for good very soon. That’s already happened with some music venues – they couldn’t find a way to survive the crisis.

Many of your plays, like 2006’s Enjoy, touch on the “lost generation” in Japan, who came of age during the recession in the 1990s, and deal with the topics of precarious work and unemployment. Are you worried the coronavirus pandemic will cause a new economic meltdown that will long impact Japan’s youth?

Yes, I am worried. The 1990s were a turning point in Japanese society – back then I was in my twenties. Before that, Japan was very comfortable economically. People thought this growth would just continue for all eternity but the recession shattered this illusion. People changed their outlook: they stopped believing in the myth of a strong Japan. Even now, I guess some people in their 60s and 70s still believe in the revival of Japan. I’m more sceptical. I think this has led to a generational divide.

The current crisis also forces us to challenge our vision of the world. Some see it as a chance: to question neoliberal ideology, the sanctity of the markets, our fast-paced lives. Is this just naïve thinking or are you optimistic too?

I can only speak from personal experience: at the moment, my way of living and thinking has changed a lot. Fortunately, I have actually been able to enjoy the past month. Spending my days like this is what I’ve wanted to do for a very long time. I’ve been far too busy. Now, I have a lot of time to reflect, to read, to be alone. It’s good. This situation is helping me to think differently. It’s encouraging me to discover new things and find new ways of doing things.

For example?

For example new forms of theatre. My company and I are currently developing a new format. It’s not theatre in a traditional sense, but rather a video installation that takes its cue from theatre in terms of framing and thinking. We wanted to work on something similar anyway, but now it’s come about by accident: this is the perfect time to experiment, to invent and discover new forms of theatre. We can expand the very idea of theatre and apply our experience and knowledge in new ways. We don’t have a venue to show our performance at the moment, so we need to go online. We are still eager to express ourselves artistically, even in the crisis. We want to make things.

Do these new digital forms of theatre also have limitations?

Yes, of course. One very important aspect of theatre is the space of the venue in which people are gathering. But I also like to think of theatre as a fictional phenomenon that takes places between performers and audiences. Theatregoers know a lot about this way of generating fictional phenomena. So we can definitely do it. And for now, we only have an online space.

Lockdown and quarantine also have a big impact on mental health, which has long been a taboo topic in Japan. Is this changing during the pandemic?

My personal impression is that Japanese people are starting to see the topic of depression as less of a taboo now because so many people are confronting their mental health. But before the crisis, as I touched on in The Vacuum Cleaner, the topic of Hikikomori people ceased being such a taboo – it was becoming impossible not to talk about it, because it simply affects so many people.

Hikikomori could be translated as “acute social withdrawal”. It describes the phenomenon of reclusive people in Japanese society. Studies put the number of Hikikomori at over half a million. The term feels particularly relevant during the current crisis, marked by social distancing and quarantine…

There are many different layers to the phenomenon but I think social warmth is one of them. From a Japanese perspective, when I go to Western countries, to Germany for example, I immediately notice their way of interacting with other people. They show their intimacy very openly. They’re a lot closer with one another than we are in Japan. Even before the coronavirus pandemic, Japanese people would rarely hug each other or even shake hands. I prefer the Western way of showing intimacy. But nowadays, even you are keeping your distance. That’s interesting. I’m curious to see how The Vacuum Cleaner works in this situation as a stream and in the context of the pandemic. All of us are suddenly faced with a completely new reality we’ve never experienced before. It’s interesting because everything can be seen in a new way.

Hikikomori is often considered a Japanese phenomenon but in The Vacuum Cleaner, you universalise it. Do you see it rather as a logical consequence of global capitalist alienation?

That’s an interesting question. I’ve done four projects with the Münchner Kammerspiele now. In each one, I brought an issue within Japanese society with me. But it’s not enough for my pieces to just convey what’s happening in Japan right now. I bring specific topics from my home country but they could happen anywhere – or at least in Germany too.

From a Japanese perspective, when I go to Western countries, to Germany for example, I immediately notice their way of interacting with other people. They show their intimacy very openly. They’re a lot closer with one another than we are in Japan.

Do you feel as though the reception of your work is different in Europe and Japan?

I like to see the interaction between an artwork and its social context. In Japan, I can anticipate that context to a certain extent, as I know what Japanese society is like. But that becomes more difficult when I produce elsewhere. So the reception of my work is certainly different in Japan and Europe but there are so many cultural reasons for this. The context of the Münchner Kammerspiele is certainly very different from any other theatre context in Japan.

In Japanese, you use a lot of youth slang, idiosyncrasies and play with colloquial speech rhythms. How does this translate into German? Has it been difficult directing in another language?

I can’t speak any German but I don’t have to in order to know that it’s impossible to completely translate the Japanese language into any other language. Certain things inevitably get lost on the way – especially the humour. But ultimately, I don’t really care. I’m happy that I’ve reached a stage where I can just write my texts in Japanese without caring about how much translation reduces the unique taste the Japanese language has.

This surely adds another dimension to the dislocation between language and body language in your work…

Body movement can be a completely separate track within the performance. That’s one of the most important things for me when producing theatre. In order to realise this alienation between speech and movement, I have a methodology. Imagination is always the most important thing in the creative process. I’m always asking actors to enrich their imagination because imagination can make your body move. Imagination is a choreographer – you need to ask it to move your body.

Final question: what do you miss most during the current crisis?

I miss my packed schedule. Being busy isn’t all bad.