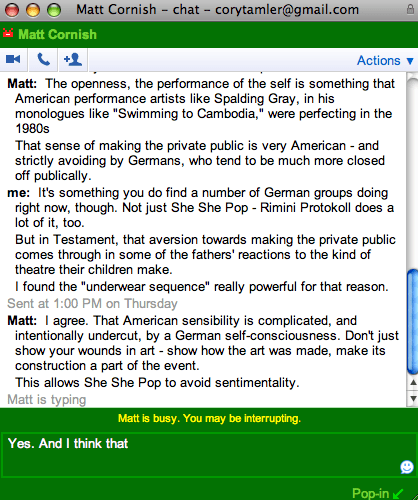

In Testament, the performance group She She Pop brings their own fathers onstage. Through questions, through songs, and through re-enactments of rehearsals, phone calls and arguments, She She Pop uses „real“ material to explore the „real“ generational shift happening in their „real“ lives. After seeing the show, Matt and Cory shared thoughts through a „real“ GChat session.

Cory: Okay. Let’s talk about Testament. My mom read Leo’s interview with one of the fathers, and she’s jealous. She wants me to do a production with moms.

Matt: Well, She She Pop is not planning a production with mothers, so it’s open for you! Your mom was able to read Leo’s interview in German?

Cory: Yes. She lived in Germany, years ago.

Matt: Cool! I didn’t realize until yesterday that the German word „Testament“ is not the same as the English testament, which has a much broader definition.

Cory: What is it specifically in German? Testament as in, will?

Matt: Yup.

Cory: While in English it can mean a lot more. Tribute, for example. Or statement.

Matt: And I found the performance itself to actually have quite an American feel to it.

Cory: Sure. And you can definitely see it in association to all of those English meanings of „testament.“ What did you find American about the production?

Matt: The openness, the performance of the self is something that American performance artists such as Spalding Gray, in his monologues like „Swimming to Cambodia,“ were perfecting in the 1980s. That sense of making the private public is very American – and avoided by Germans, who tend to be more closed off publically.

Cory: It’s something you do find a number of German groups doing right now, though. Rimini Protokoll does a lot of it, too. But in Testament, that aversion towards making the private public comes through in some of the fathers‘ reactions to the kind of theatre their children make. I found the „underwear sequence,“ where one of the fathers criticizes the group for exposing their bodies during a previous piece and then strips down to his boxers with the other fathers, really powerful for that reason.

Matt: I agree. That American sensibility is complicated, and intentionally undercut, by a German self-consciousness: Don’t just show your wounds in art – show how the art was made, make its construction a part of the event. This allows She She Pop to avoid sentimentality.

Cory: An American version of Testament would have a hard time keeping itself so bare and presentational. Not in the sense of production values, but in the feel of the performances themselves. It’s almost as if their way of dealing with making their private selves public is to keep it objective. The material is subjective, the presentation objective.

Matt: That reminds me of one of my favorite moments in the piece, which handled this private/public problem explicitly: during the “songs sequence,” when the fathers and daughters (or son) sat down to listen to a record together. We could tell that the songs had specific meanings for them, holding much emotion and memory. But we weren’t told about those memories, we didn’t actually get to experience them voyeuristically. We only got a glimpse into their subjective experiences, while the material itself was handled objectively, making it even more powerful in the end.

Cory: I think it would be easy with a piece like this to fall into making the audience voyeurs, but they don’t do that.

Matt: Though one of the fathers worries aloud about the piece becoming pure voyeurism!

Cory: And it’s exactly because they’re so open about sharing that, that they avoid the pitfall. Everyone I talked to after the show said they’d asked themselves while watching, „Would my father do this?“ Or, „Would I do this with my father?“

Matt: Well, I’m not sure if I would do something like this with my father, but I would enjoy seeing it with him.

Cory: I felt the same way. My dad’s a big ham, though. He’d probably be all about doing it.

Matt: As the members of She She Pop and their fathers said in the talk-back – this is art, not therapy. I feel like the performance is more for the audience than for the participants.

Cory: Absolutely. And I think the simple question „Would my dad do this?“ leads to more complicated questions – Would I have these conversations with my dad? What would his answers be? What does my dad think about getting older?

Matt: And what will I inherit? Not just the physical items, hilariously listed during the performance, or even love, which Lear desires in exchange for passing down power and property. We also inherit mannerism and expressions, pasts that shape our futures. And you could see this in the interactions of the participants. These pasts – like the Silesian dialect one of the fathers talks about – become incredibly important as we grow old.

Cory: Since it’s not for therapeutic purposes, what do you think this interaction between the „real“ parents and children brings to the performance? Why is it important that the relationships be „real“? („real“ in quotation marks, because as the performers point out, they’re all playing roles even if the roles are themselves.)

Matt: Maybe it forces us to think more specifically about our actual interactions in the world we share with our fathers. This is of course also a world of role playing. It also allows us to think about the nature of art itself – it stages its artfulness in a way that King Lear does not. So that we confront the contradictions of relationships and thinking about those relationships in large groups – which, of course, is what theater does.

Cory: For me, it really brings something to see the openness they achieve with one another. The fact that the relationships are real means that there was potential for real strife, real hurt; that real shame had to be explored, real differences.

Matt: And though they couldn’t „re-stage“ those real fights, they allowed us a peek at them by speaking aloud from tapes of rehearsals.

Cory: Though maybe they should have re-staged them. The OC: Berlin!

Matt: I would watch that all day long!