Last night was the launch of the Theatertreffen Stückemarkt, the play competition that takes pride of place in the festival’s supporting programme. Over 300 playwrights from all over Europe entered this year, and for the first time the competition was also opened up to collectives, or ‘project developers’. Staged readings of the five chosen plays are performed to paying audiences (the Markus & Markus collective will also show their piece, but it’s difficult for anyone – including them – to say what form it will take at this point), and on Monday three prizes will be up for grabs: the Advancement Award for New Drama, the Theatertreffen Writing Contract, and the Radio Play award.

Stückemarkt Director Christina Zintl, Photo: Nadine Loës

The launch of any TT12 event necessarily means a minimum of three speeches, starting with a hushed introduction from the Head of the Festspiele Thomas Oberender, in this case passing us over to Heinz Dürr, creator of the Dürr Foundation and donor of the Advancement Award. Then just one more to go – Christina Zintl, director of the Stückemarkt, who welcomed the playwrights and project developers to the festival. What they all have in common, she stated, is that they are all aware of the standpoint they are presenting, and it is this awareness that she would describe as political.

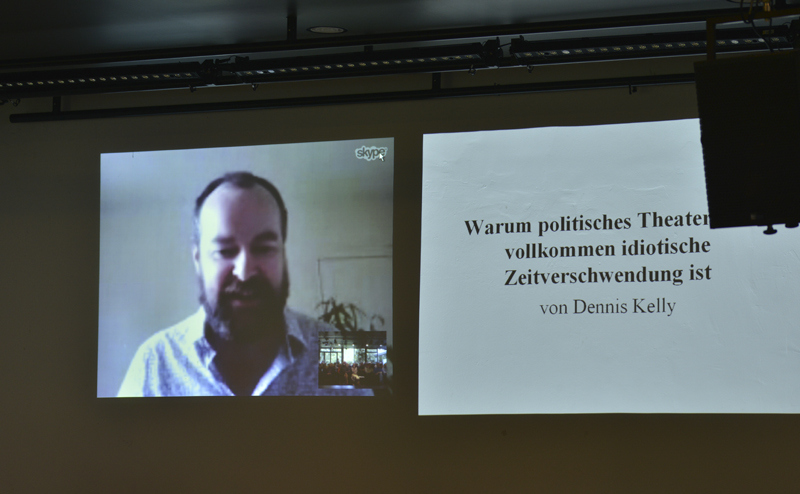

My ears prick up at the word “political” – surely it must be time for Dennis Kelly’s opening speech. Via Skype, due to personal reasons that prevented him from coming over from London, he announced that he’d been told he would be addressing a group of young, politically engaged playwrights – so naturally he wrote a speech entitled: “Why political theatre is a complete fucking waste of time.”

Dennis Kelly, thanks to Skype, Photo: Nadine Loës

You can read the full (very entertaining) text here, but I’ll summarise the key points:

– A writer mustn’t exploit a political topic for his or her own ends.

– A writer must aim to convey truth.

– Swearing is fun.

Riemenschneider's blackboard, Photo: Miriam Sherwod

It’s hard to guess what Kelly’s impression would have been of the night’s first reading. Wolfram Höll’s Und dann, which won the 26-year old a prize for best up-and-coming author at the Heidelberger Stückemarkt earlier this month, didn’t have any swearing in it for one thing. The play almost takes the form of a child’s stream of consciousness, but written on a typewriter, where deleting is a much bigger deal than simply pressing backspace (which I did at least 30 times just in writing this one sentence). There are no delineated roles in the text; instead Höll plays with the alignment of the words of the page, creating a script that could be seen as a work of art in itself.

The text was split into three parts for the reading, based on the characters that emerge – Vater, du and ich. Alexander Riemenschneider’s decision to sit the three actors on a wall was somehow charming in its simplicity, and his staging reflected the visual layout’s importance in Höll’s writing – as a finale, a fan was turned on and the actors threw the loose pages of their scripts into the air, huddling closer to read the one final page together.

For a reading this idea worked really well, although you have to wonder how it would work in a fully-fledged performance. Then again, being left wondering is by no means a bad thing. Who knows, it could result in an exciting production.

Wolfram Höll (2nd right) takes a bow with the actors, Photo: Miriam Sherwood

Höll plays with the musicality of language, using repetition and assonance for all he’s worth. At its low points this came across a bit like a broken record, but at its best it was the endearing sound of a thought trying to articulate itself, and you could feel the “current” he described in the post-show talk, pulling him along through his “rhythmic, mechanical dance across the typewriter keys.” A shoo-in for the radio prize, maybe? You can hear Höll talk about the play here.

Doodle: Miriam Sherwood

Skåne by British playwright Pamela Carter closed the evening with thunderous applause, in particular for the three young actors who played children their own age, caught up in the destruction that a passionate affair wreaks in their families. Karin Neuhäuser staged the reading in a press conference format which was perfectly suited to the forced, formal meeting between the two families that opens the play. The stage directions were read aloud too, which I don’t think I would have minded had they been a bit more audible. Lenz Lengers as the 10-year old Olle stole the show, not only with his ridiculously adorable attempts to keep a straight face when the audience laughed, but with his ability to eventually tune all of that out and give an impressive performance.

The press conference, Photo: Miriam Sherwood