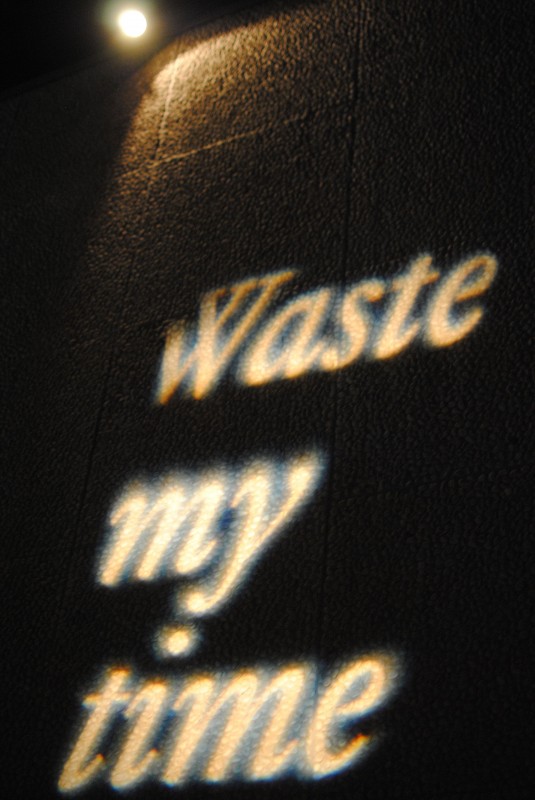

After the jury’s selection was announced, Theatertreffen director Yvonne Büdenhölzer named two defining features of this year’s choices: “Collective” and “Time.” Interestingly, the latter was expressed in a deliberately negative way by the festival itself: The phrase “Waste My Time” is projected against the back wall of the garden where audience members and theatre makers mingle every evening after the performances. The official discussion on the topic, which took place this Tuesday, bore the same attention-grabbing title.

Projection in the TT Garden, Photo: Miriam Sherwood

The trigger for this discussion is one particular kind of time: running time. That is to say, the length of the invited productions. Platonov: 5 hours. Faust I+II: 8 hours. John Gabriel Borkman: 12 hours. The Kane trilogy barely gets a look-in with 3.5 hours, which at least by U.K. standards might already be pushing it. Several of the other performances, by contrast, are much more on the succinct side. Hate Radio runs to 90 minutes, Before Your Very Eyes and Kill Your Darlings! to only 70. Those left (Macbeth, Die [s]panische Fliege, Ein Volksfeind) all stick to a relatively compact 2 hours.

At the “Waste My Time” talk, the discussion focussed on the XXL productions. I collected some clues as to what might be the cause of this apparent tendency from speakers Nicolas Stemann (director of Faust I+II, the “marathon”), Florian Opitz (director of the 2011 film “Speed: In Search of Lost Time”), and theatre theorist Kai van Eikels. And, as time is of the essence, here’s a summary of why they thought these performances take their time:

The artist’s perspective (Stemann and Opitz):

– An attempt to create a piece of theatre that is a part of life

– The creation of a shared experience, not just among the audience members but also between audience and performers

– A reaction to the feeling that time is controlling our lives

– A rebellion against the demands of bums-on-seats theatre culture, which is afraid to take a risk on a large project that might not be an economic success

– A way to reflect or show the reality of creating a piece of theatre and to demystify the theatrical process

The academic’s perspective (van Eikels):

– A style of theatre that goes back to Ancient Greece, when day-long performances of tragedies were a perfectly common way to pass the time

Whichever side you chose here, the question remains: what’s with the negativity, TT? Obviously a theatre festival isn’t seriously suggesting that theatre is a waste of time, so isn’t it just a case of the more the better? Apparently not:

The main side effect of temporal obesity raised by panellists and audience members was the movement away from conventional storytelling. The human attention span is not used to such endurance, so more intervals or a “come and go as you please” policy are required. Once the full attention of the audience is not needed or assumed, then the importance of an actual “story” (with character development and an arc from beginning to end that has to be followed closely) is lost.

Here again the academic added a nice helping of historical context: In Shakespeare’s time it was taken for granted that people walked in and out of performances, ate, drank, and heckled. Even prostitutes roamed the aisles. In Ancient Greece it was the same because it was assumed that everyone already knew how the story would end – after all, a tragedy can only end one way. But van Eikels highlighted a negative consequence too, citing Brecht as a believer that this multi-tasking approach (the original example was watching a piece of theatre whilst smoking a cigar) would be the death of theatre, as it creates a gulf between the spectator and the performance.

Both these proposed losses (of a story, and of a connection to that story or performance) could be debated extensively. Unfortunately they weren’t, because the discussion ran out of time.

It strikes me that one huge negative has been ignored entirely. I mentioned the extra-long performances such as Borkman casually in several of my early posts, always with the negative connotation of “how am I going to survive this?” But I already knew I had a ticket to those shows, and that it would be my job to go and find out if they were survivable. To most people who don’t make their living in the theatre industry, or who aren’t used to sitting through whole days of Wagner, the fact that a performance is 4-12 hours long is extremely off-putting. It might sound obvious, but isn’t it the case that, thanks to this trend, you now not only have to have the money to buy a theatre ticket, the means to get to the theatre (if it’s a “Stadt” or “Staatstheater it’s guaranteed to be in the centre of town, probably in an affluent neighbourhood), and the inclination to go in the first place, but you also need to have a lot of time to spare?

Maybe the XXS productions in this year’s selection are a reaction against that. Then again, let’s not forget that time in the theatre is just as subjective as anywhere else: As we found out last night, 2 hours of Ein Volksfeind can feel a lot longer than 8 hours of Faust I+II.