The final Theatertreffen 2012 production to premiere is the black sheep of the family. All its other relatives have been and gone, throwing paint on the bare walls of their sets, chatting to their audiences and, in certain isolated incidents (that crazy Uncle Vinge), urinating on their actors. Now all of a sudden, Platonov shows up and rocks the boat with the ultimate rebellion: Naturalism.

(Well, the definition of “naturalism” is highly debated, but in the case of Chekhov I’ll take an old-school one from the first main spokesperson for the style, author Emile Zola: “We simply take from life the story of a being or group of beings whose acts we faithfully set down. The work becomes an official record, nothing more; its only merit is that of exact observation.”)

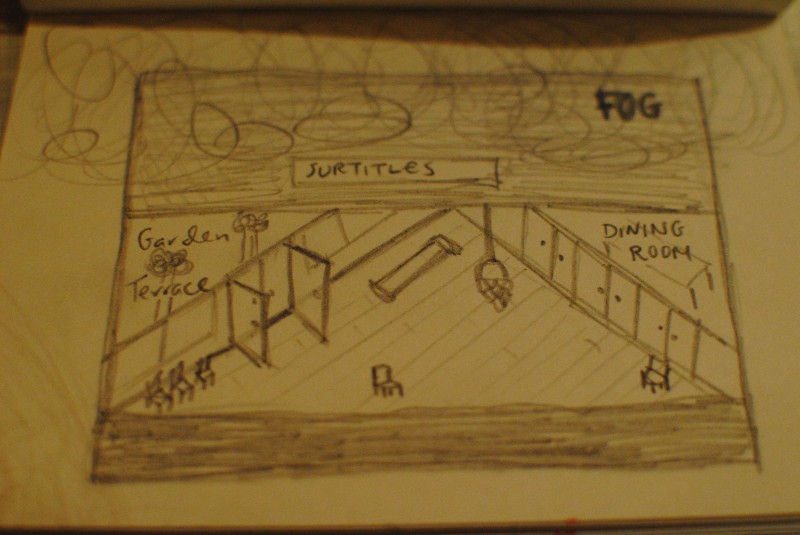

As the audience entered the theatre, they probably rubbed their eyes in disbelief. Rather than using the text as a loose structure or idea on which to base the production, director Hermanis has read Chekhov’s stage directions, and Monika Pormale has translated them onto the stage in an “exact observation.” We see a large room, connected through one central door to a terrace and garden on the one side, and separated from a dining room on the other by a wall of transparent doors. Both of these extra spaces are somewhat obscured from the audience’s sight. I’m no expert on late 19th Century Russian furniture, but it certainly seemed like every detail of the set and costumes was historically accurate.

Here’s a rudimentary idea of what it looks like:

Platonov set design, Doodle: Miriam Sherwood

(And here’s a sophisticated one.)

Pormale has created a beautiful cross-section of a completely different time. It feels as though Hermanis and his team have given everything they’ve got to create a production to match it, and if you ask me, they succeeded. I’m not going to lie – I struggled in the first act. Keeping up with the constant stream of characters, each referred to by a different name by each of the other characters, was made all the more difficult by the fact that everyone always entered through the garden or the dining room, so often the introductions or opening comments were too distant to be followed. Even once they entered the main room facing the audience, it was no guarantee that the actors would be any more audible, as the naturalistic style allows them to turn their backs to us, to mumble – to do whatever feels natural. Twice there was a clear summons from the audience to “Speak up please!”

But from Act II onwards things only got better. This may have had something to do with the addition of alcohol. It appears that Chekhov’s first play is basically about a big group of friends and relatives, the female contingent of which are mostly in love with Platonov, getting excessively drunk together. Perhaps even more surprisingly, it’s funny. I studied Chekhov’s Three Sisters at school and they were forever telling us that the playwright saw his plays as comedies, not tragedies. Yet there has rarely been a production of that play where I’ve laughed, or thought anything much other than “FOR GOD’S SAKE JUST GO TO MOSCOW THEN.” Not so in Hermanis’ Platonov: The cast are excellent drunks. A scene between Martin Wuttke as Platonov and Fabian Krüger as Isaac Abramovič in the middle of this debauched night, in which the latter seeks relationship advice from the former, who spends the entirety of the scene simply trying to get comfortable on a narrow couch but seems unable to get rid of his new friend Isaac, made me laugh more than any other scene performed at this year’s festival.

The drunkenness also gave the opportunity for lots of touchy-feely behaviour from characters normally laced up in their corsets and good manners. Hermanis creates comic piles of different constellations of actors that feel both unexpected and organic. Despite the size of the cast, there is no weak link to be found in the acting. The only slightly strange thing is a question of casting: Whilst Martin Wuttke plays a convincing Platonov in terms of the character’s battle with his own cynicism and fear of being loved, he is not “the most beautiful husband in the world … dazzling in the moonlight … a man who all the women in the world would pursue” in the classical sense. At times, the fact he was being pursued by four different women all constantly gushing these compliments seemed like a stretch of the imagination that was counter to everything else in the production. Then again, it certainly made the whole play a lot funnier, and it’s true that as much as they sing his praises, he is just as often referred to as an “oddball”…

Johanna Wokalek (Sofja Egorovna) and Martin Wuttke (Platonov), Photo: Georg Soulek

Part of the reason the characters are so well developed is down to the set. Initially I was worried that the design might be over-indulgent, an attempt to build a fourth wall between the performers and the audience that was so solid and high that we would never be able to see over it. Instead, I felt the large amount of space and variety of locations was key to opening up the range of the actors’ movement and giving them a freedom that leads to truly three-dimensional characters. I’ve seen a few productions that tried to create this kind of “lifelike” space on stage, complete with semi-hidden rooms and actors talking over each other, but none managed to achieve what Hermanis has, giving the audience freedom too. As a spectator, more often than not it’s up to you to decide what “scene” to observe; perhaps the conversation downstage doesn’t interest you, but the possible flirting happening on the terrace does.

The production isn’t weighed down by its historically accurate props and furniture either, thanks to the fact that the main, open room was light and bare of anything except a few chairs and a sofa. Rather than letting clever nods to “the olden days” govern the set, Hermanis makes a feature of Pormale’s many doors. Hostess Anna Petrovna Vojniceva (played by Dörte Lyssewski) is first seen standing in front of the door to the garden, waiting for Platonov. As the play progresses, the theme transforms from arrival to departure, ending with Platonov’s death as he stands in that very same door frame. In between, the doors act as protection, something to hide behind, to exclude unwanted company with, a support to lean against, a frame to appear in and seduce from, and a safety net – a way of avoiding confrontation with the truth, by not having to cross over the threshold. All these games the characters play with the set emphasize the different rules they are trying to play by. Everybody wants something, but only if they can get it on their own terms: “Say what you want – but don’t ask questions,” Platonov says to Anna Petrovna.

Hermanis creates a slice of upper-class Russian life in collapse using nothing other than the original script (in an atmospheric translation by Peter Urban), a brilliant cast of team-players and some masterful staging decisions. It’s possible to say all this has been done before – but at least in the case of Theatertreffen 2012, it wouldn’t be true.