Annegret:

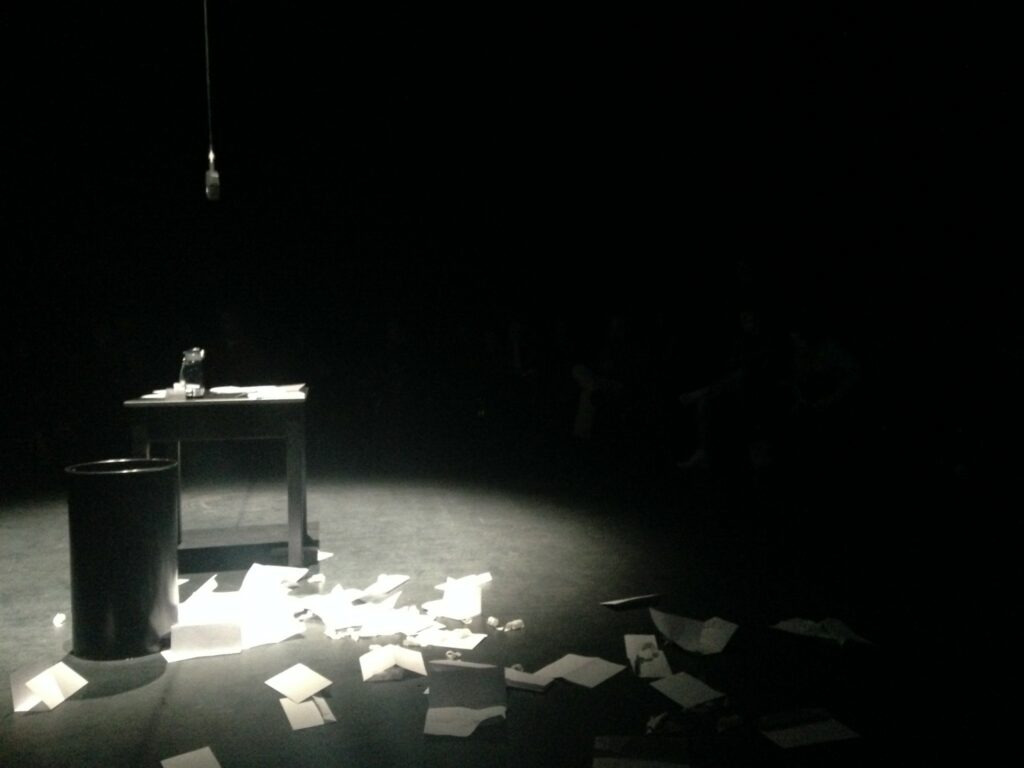

There’s a black table with a square pit in the middle. It contains a stack of envelopes. A stark spotlight illuminates the table, and a microphone dangles from the ceiling. We’re seeing “The State” by Bulgarian playwright Alexander Manuiloff. Well, we’re not exactly seeing it. We’re participating in it.

We’re expecting it to start but it won’t. A few minutes go by. Silence stretches. The audience, sitting in the round, wait and look at each other expectantly. It just won’t start. Finally, a man in a bright red sweater stands, approaches the table, picks up an envelope, opens the letter and reads it aloud. “The performance will start in 8 hours and 5 minutes,” he says.

I’ve never wanted the audience to mess with a performance so much as with this one. “The State,” invited to the Theatertreffen Stückemarkt – a showcase of new works by young European writers – is a participatory piece without actors or instructions. The piece attempts to tell the story of a Bulgarian man named Plamen Goranov who died from self-immolation. It also questions conventional theatre viewing habits within the theatre space by drawing parallels between audience behaviour and methods of participation within a democratic political system.

It took a few minutes for the first person to gather the courage and walk centre stage to take action. When were you first compelled to participate? Did you feel like you had to?

Rebecca:

I was tempted to leap up from the get-go and open one of the envelopes. But I also knew that’s what was expected of us (I’d read the first page of the script), so in the name of theatrical purity or something similarly bogus, I decided to leave it to someone else. If I were to stretch this, maybe that’s the equivalent of assuming someone else will speak out against wrongdoing – the bystander effect.

In our room, where things were in English, about six minutes passed before the first audience member approached the table to open an envelope. (The German-language room took only two-and-a-half minutes, we learned later.) I hopped up after another five or so minutes, after I grew tired of observing the curious practice of tossing the envelope into the wastebin and leaving the paper on the table.

By this point, though, it had already become clear what awaited us in the letters. Half described how the performance would be starting later – in 6 hours, in 8 hours and 5 minutes, in two hours and 45 minutes – or could not happen because we didn’t have a director, or because the lead actor was missing, or because the show didn’t comply with shady government regulations, or whatever. The other half were first-person missives from Plamen. Some were banal. Others detailed his plans for self-immolation. (Though Plamen was a real guy, the letters are Manuiloff’s creation.)

The first envelope I opened was one of these messages from Plamen. Plamen, we learned, was well-liked. He went shopping for his 90-year-old neighbor. He liked to take walks along the river.

I found the content of the notes less interesting than what was actually happening in the room – how people were working to create structure or to rebel against it. It was quickly clear that Plamen was protesting political corruption, and that the endless “postponements” of our “performance” were also repression. That struck me as a (too?) blunt context for addressing questions of agency and participation and authority.

But the papers have to say something, right? Were you drawn to the text? Or what moments did you find engaging or surprising?

Annegret:

I agree that in light of the experimental structure, the content of the notes became secondary. I think it’s highly problematic that Plamen’s story got lost (sacrificed) amid examining and making a statement about negotiating collective debate in artificial spaces. This would have been different had the main character been fictional, but he was a real person who died in horrible circumstances while protesting mafia-like structures in Bulgaria.

It’s not the first time at this Theatertreffen that real people’s fates were ancillary to making a point about the structure of theatre. “Die Schutzbefohlenen,” too, spent an awfully long time addressing the limitations of theatre and the connections between theatre and society, which detracted from a straightforward account about – and from – the refugees. The crucial difference, however, is that I don’t think Manuiloff intended to drown out Plamen’s story, while director Nicolas Stemann’s version of Elfriede’s Jelinek text drowned out the refugees‘ stories very deliberately.

To be fair, it’s not the author’s task to educate us about a topic. I’ll be the first to recoil from didacticism. Hell, I could have looked up Plamen’s biography on Wikipedia right there and then during the performance – who would have stopped me? From our audience, probably no one – considering a woman walked out with a stack of unopened letters and no one held her back.

The moments that were immediately perceived as disobedience against unspoken rules were the most intriguing: someone upending the dustbin with discarded envelopes, someone refusing to read out a letter they had taken from the pile, someone setting fire to a letter – a symbolic action if there ever was one – and being promptly asked by a member of staff to put it out (someone else extinguished it, and left their water bottle on the table).

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von YouTube. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

This doing and undoing, and all these moments of disobedience, were fascinating to watch and certainly surprising from a sociological perspective. At the audience talk afterwards, we learned that, rather stereotypically, the German-language version of the piece proceeded in much more orderly fashion. They certainly had no one jumping into the circle pretending to be a chicken. When that happened in our room, I was utterly bewildered. What question does the space pose to the audience? How do we perform in situations where we know we’re being watched? Was the setup actually a good metaphor for how democracy works (and fails)?

Rebecca:

I struggled to see „The State“ as a metaphor for democracy. Some reasons are obvious: It was 45 minutes with about 30 others, not a grindingly slow process with millions of anonymous people. But I was also frustrated with the way the texts demanded we see this as a political experiment, rather than leaving things more open-ended.

Which, of course, is not to say theatre should never be frustrating. It was interesting to observe my own irritation and that of others around me. After an initial rush to tear open the envelopes, I sensed a decrease in curiosity – we knew what they’d say. Some people reacted to this repetition by exchanging exhausted glances. Another man, as you’ve said, squawked around the room like a chicken, and later buzzed around like a fly. But it struck me as a theatrical act, not a political one. (Or is that an unfair distinction to make?) Even though we knew this was a non-traditional piece of theatre, everybody expected some sort of performance, and he attempted to fulfill that expectation. (I found myself squirming from vicarious embarrassment.)

But back to the texts for a second – they were heavy-handed, yes, but also angry, and this anger seeped into the audience. When a woman silently took a letter back to her seat, someone else asked her, very politely, to read it. “Why?” she answered, in an impertinent tone. In the German-language version, an audience member apparently kept a running (and disdainful) commentary from her seat, which upset other people. In our room, a few people acted in bold ways, but no one really talked. There were only a couple moments when anyone offered up their own words.

A few years ago, I took part in another piece of participatory theatre – Ivana Müller’s “We Are Still Watching” – that fostered humor and a sense of community. That was definitely not the case here, and I found myself wondering about this combativeness. Weren’t we in this together? Aesthetically, I think the space encouraged antagonism. It recalled an interrogation room – bare-bones, with a single table and an aggressively bright spotlight. Not exactly a friendly setting. And it was hard to see other people’s faces, so there was a sense of anonymity.

What did you think of the mood in the room? Could you sense people’s anger when the woman grabbed five or six envelopes and left the theatre with them? I thought it was an intriguing, brash move, but afterwards several people seemed genuinely upset about it. (Maybe they were holding onto a hope that one of those envelopes would contain a radically different text…) Did they think she’d overstepped the bounds of “appropriate” participation? If we’ve already been at the mercy of an anonymous ruler (unspoken social norms? The general rules of the theatre? Manuiloff?), how do we react when one of “us” seizes control in that way?

Annegret:

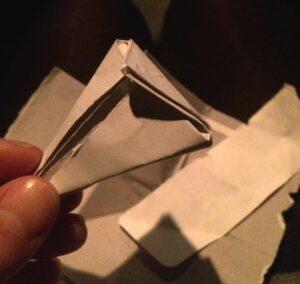

Some people said they interpreted her move as an act of violence, defying the structure that had been set up, but to be honest, I didn’t even notice her taking the envelopes and walking out. Like you and other members of the audience, I became exhausted and disinterested. In one of Plamen’s letters, there was a mention of a bird, and I started trying to fold a paper crane out of one of the envelopes. I think I spent at least 20 minutes on this task, which ultimately failed spectacularly. I think it was my way of withdrawing from the monotonous structure and the “it’s-your-turn”-way of dealing with the envelopes. It felt incredibly liberating, but I was on my own in that experience.

Failed Pelican

Maybe other people created these moments for themselves, too? But what a bleak outlook on society: Structures were only challenged on individual terms – here, mostly silliness or defiance – not collectively.

Unlike other participatory theatre I’ve seen, this one felt much less empowering. But that was perhaps intentional, seeing as it dealt with oppression and the shortcomings of our political systems. When I saw Kaleider’s „The Money” at Battersea Arts Centre in London, a real discussion took place. Not just around the topic, but also on a meta level about the processes with which the piece concerned itself namely decisions about spending and doing good with money.

On this evening, and with this audience, “The State” ultimately failed to do that. I wanted rebellion, not resignation.

Rebecca:

I’ve got some rebellion for you. Later that evening, I received a text message from a friend who was also at the performance. “I am an American playwright,” she wrote. “Tomorrow at 5:00 pm I will burn myself alive.”

The State

by Alexander Manuiloff.